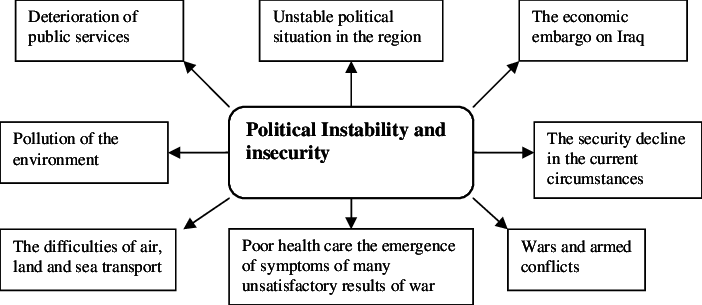

Sources of instability

THERE is an enduring debate on the degree to which politics reflects a country’s societal trends. Some analysts argue that politics usually reflects deep divides or cleavages found in society, such as socioeconomic class, religion, ethnicity, or gender. Others argue that political actors actively make or break identities and divisions in society, which helps them win power.

As is usually the case, the truth lies somewhere in the middle. Sometimes it takes a while for political parties to wake up to societal truths and trends. Societies undergo demographic and economic shifts and change people’s requirements from politics. But parties can be slow to act.

Other times, political parties try to act contrary to society’s existing divisions. They attempt to create new visions of a society, ignoring inequities, imbalances, and pre-existing fault-lines.

When there is a gap between people’s expectations from politics and what political actors are usually doing, it leads to moments of crises. The crises can be violent upheavals. Or they can be episodic bursts of instability because of infighting among politicians, between politicians and groups of citizens, or between politicians and other state institutions. But all three are a sign that state and society will have to adapt for stability to re-emerge.

Pakistani politics, especially in the mainstream, demonstrates gaps with society fairly frequently. Over the last decade and a half, we can see three variants at different points in time: 1) new ways of thinking about an issue become popular in society so the state and political parties belatedly try to co-opt it; 2) the state and political parties attempt to coercively centralize authority and enforce unity despite the existence of different and competing interests in society; 3) the state and political parties ignore deep demographic and economic transformations in society and try to carry on with business as usual.

All three types of gaps have produced their own type of instability.